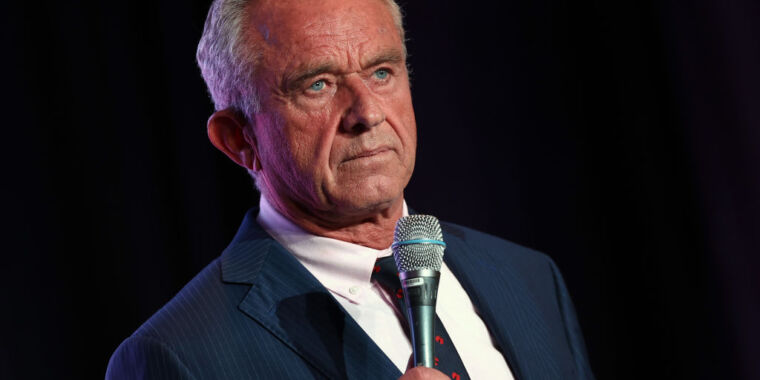

The Children’s Health Defense (CHD), an anti-vaccine group founded by Robert F. Kennedy Jr, has once again failed to convince a court that Meta acted as a state agent when censoring the group’s posts and ads on Facebook and Instagram.

In his opinion affirming a lower court’s dismissal, US Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Eric Miller wrote that CHD failed to prove that Meta acted as an arm of the government in censoring posts. Concluding that Meta’s right to censor views that the platforms find “distasteful” is protected by the First Amendment, Miller denied CHD’s requested relief, which had included an injunction and civil monetary damages.

“Meta evidently believes that vaccines are safe and effective and that their use should be encouraged,” Miller wrote. “It does not lose the right to promote those views simply because they happen to be shared by the government.”

CHD told Reuters that the group “was disappointed with the decision and considering its legal options.”

The group first filed the complaint in 2020, arguing that Meta colluded with government officials to censor protected speech by labeling anti-vaccine posts as misleading or removing and shadowbanning CHD posts. This caused CHD’s traffic on the platforms to plummet, CHD claimed, and ultimately, its pages were removed from both platforms.

However, critically, Miller wrote, CHD did not allege that “the government was actually involved in the decisions to label CHD’s posts as ‘false’ or ‘misleading,’ the decision to put the warning label on CHD’s Facebook page, or the decisions to ‘demonetize’ or ‘shadow-ban.'”

“CHD has not alleged facts that allow us to infer that the government coerced Meta into implementing a specific policy,” Miller wrote.

Instead, Meta “was entitled to encourage” various “input from the government,” justifiably seeking vaccine-related information provided by the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as it navigated complex content moderation decisions throughout the pandemic, Miller wrote.

Therefore, Meta’s actions against CHD were due to “Meta’s own ‘policy of censoring,’ not any provision of federal law,” Miller concluded. “The evidence suggested that Meta had independent incentives to moderate content and exercised its own judgment in so doing.”

None of CHD’s theories that Meta coordinated with officials to deprive “CHD of its constitutional rights” were plausible, Miller wrote, whereas the “innocent alternative”—”that Meta adopted the policy it did simply because” CEO Mark Zuckerberg and Meta “share the government’s view that vaccines are safe and effective”—appeared “more plausible.”

Meta “does not become an agent of the government just because it decides that the CDC sometimes has a point,” Miller wrote.

Equally not persuasive were CHD’s notions that Section 230 immunity—which shields platforms from liability for third-party content—”‘removed all legal barriers’ to the censorship of vaccine-related speech,” such that “Meta’s restriction of that content should be considered state action.”

“That Section 230 operates in the background to immunize Meta if it chooses to suppress vaccine misinformation—whether because it shares the government’s health concerns or for independent commercial reasons—does not transform Meta’s choice into state action,” Miller wrote.

One judge dissented over Section 230 concerns

In his dissenting opinion, Judge Daniel Collins defended CHD’s Section 230 claim, however, suggesting that the appeals court erred and should have granted CHD injunctive and declaratory relief from alleged censorship. CHD CEO Mary Holland told The Defender that the group was pleased the decision was not unanimous.

According to Collins, who like Miller is a Trump appointee, Meta could never have built its massive social platforms without Section 230 immunity, which grants platforms the ability to broadly censor viewpoints they disfavor.

It was “important to keep in mind” that “the vast practical power that Meta exercises over the speech of millions of others ultimately rests on a government-granted privilege to which Meta is not constitutionally entitled,” Collins wrote. And this power “makes a crucial difference in the state-action analysis.”

As Collins sees it, CHD could plausibly allege that Meta’s communications with government officials about vaccine-related misinformation targeted specific users, like the “disinformation dozen” that includes both CHD and Kennedy. In that case, it appears possible to Collins that Section 230 provides a potential opportunity for government to target speech that it disfavors through mechanisms provided by the platforms.

“Having specifically and purposefully created an immunized power for mega-platform operators to freely censor the speech of millions of persons on those platforms, the Government is perhaps unsurprisingly tempted to then try to influence particular uses of such dangerous levers against protected speech expressing viewpoints the Government does not like,” Collins warned.

He further argued that “Meta’s relevant First Amendment rights” do not “give Meta an unbounded freedom to work with the Government in suppressing speech on its platforms.” Disagreeing with the majority, he wrote that “in this distinctive scenario, applying the state-action doctrine promotes individual liberty by keeping the Government’s hands away from the tempting levers of censorship on these vast platforms.”

The majority agreed, however, that while Section 230 immunity “is undoubtedly a significant benefit to companies like Meta,” lawmakers’ threats to weaken Section 230 did not suggest that Meta’s anti-vaccine policy was coerced state action.

“Many companies rely, in one way or another, on a favorable regulatory environment or the goodwill of the government,” Miller wrote. “If that were enough for state action, every large government contractor would be a state actor. But that is not the law.”