Ramsay’s experience as a prisoner was a bit different. “I don’t think any of the prisoners were conscious of the camera, honestly,” he told Ars. “We were not entirely sure where it was, we thought we saw it sometimes. But we were not getting regular instructions, we were being fed badly, clothed badly, et cetera. In a situation like that, what the camera angle is, it’s the least of your worries.”

In retrospect, the Stanford Prison Experiment may have more in common with reality TV; the industry term has evolved into “unscripted” TV because of the countless ways the final product is manipulated and shaped over the course of filming. Zimbardo even admits as much in the documentary, calling his experiment “the first ever reality TV show.”

Controlling the narrative

National Geographic/Katrina Marcinowski

The re-creation set in Los Angeles.

National Geographic/Katrina Marcinowski

National Geographic/Katrina Marcinowski

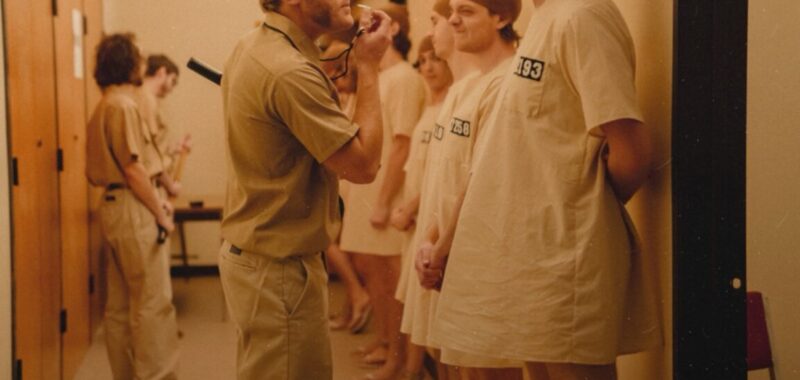

A re-creation guard on set with director Juliette Eisner.

National Geographic/Katrina Marcinowski

National Geographic/Daniel Hollis

A prop TV displays scenes from inside the re-creation set hallway.

National Geographic/Daniel Hollis

A re-creation guard on set with director Juliette Eisner.

National Geographic/Katrina Marcinowski

A prop TV displays scenes from inside the re-creation set hallway.

National Geographic/Daniel Hollis

National Geographic/Katrina Marcinowski

Dave Eshleman (right) and his re-creation double on set in Los Angeles.

National Geographic/Daniel Hollis

Zimbardo’s version of events has long dominated the prevailing understanding of the Stanford Prison Experiment, even though some of the original participants have frequently tried to counter that narrative; their voices just never held as much sway. While Eshleman has participated in many media interviews over the ensuing decades, he said that much of his commentary was often edited out in favor of Zimbardo’s preferred narrative.

For his part, Zimbardo has said repeatedly that Korpi, for instance, was lying about faking his breakdown, pointing to the fact that Korpi became a prison psychologist because of how deeply the experiment affected him. Zimbardo also denies in the NatGeo documentary that Eshleman was acting for the duration of the experiment; his interpretation is that this is how Eshleman rationalized his behavior and dealt with the guilt.

“I think I knew if I was acting or not,” Eshleman countered. “How could he not even consider the possibility that not just I, but everybody in his little demonstration was acting, that we simply fell into roles that were expected of us, to be paid $15 a day? That’s what galls me. He kind of decided to throw us [the guards] under the bus after directing us to do what he wanted. Maybe he never took an acting class. Those of those in the theater department are always acting in some way.” In fact, the basic scenario of the Stanford Prison Experiment has found its way into many improv classes as an exercise prompt.