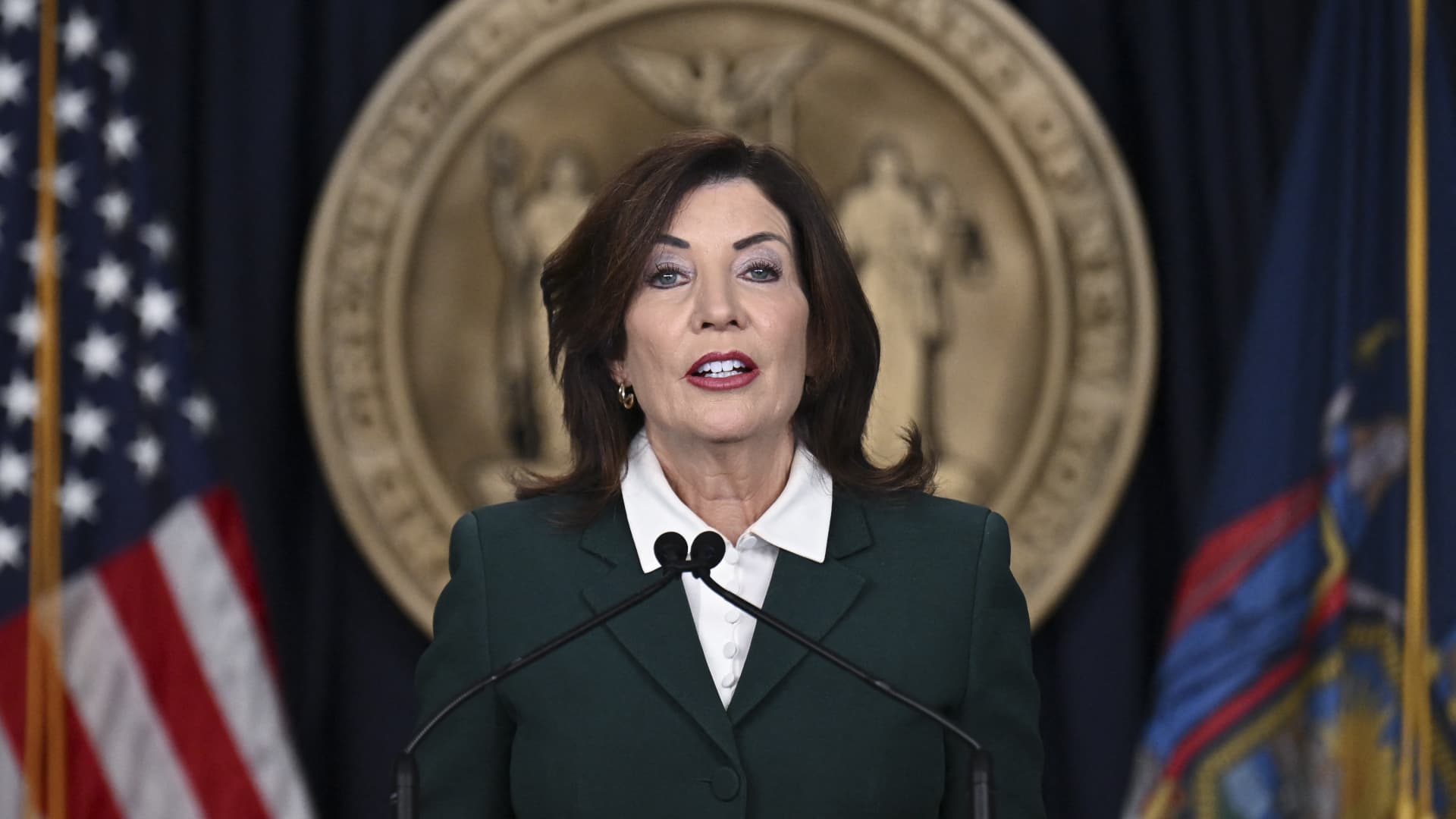

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul gave the green light Thursday to relaunch the drive for congestion pricing in New York City, a first-in-the-nation plan aimed at reducing gridlock by imposing a $9 toll on most vehicles entering the core of Manhattan during peak hours.

Hochul made the announcement four months after she put the brakes on an earlier version that would have gone into effect in June and would have charged cars $15 to enter Manhattan below 61st Street, and hit trucks with even higher tolls a few months later.

At the time, Hochul said congestion pricing at that rate would be a hardship on New Yorkers struggling to make ends meet in the post-pandemic economy.

“I believe that no New Yorker should have to pay a penny more than absolutely necessary to achieve these goals, and $15 was too much,” Hochul said Thursday at a news conference. “I am proud to announce we have found a path to fund the MTA, reduce congestion and keep millions of dollars in the pockets of our commuters.”

The lower toll will still allow officials to make improvements to New York City’s aging transit system “and begin to drive down gridlock” while improving air quality for all New Yorkers, she said.

“Years and years of disinvestment by previous administrations ends today,” Hochul said.

Now the race is on to get congestion pricing approved before President-elect Donald Trump, who opposes it, takes office in January.

Hochul was still speaking when New Jersey Gov. Phil Murphy issued a statement from the other side of the Hudson River condemning the plan and vowing to sue to stop it from going into effect.

“All of us need to listen to the message that voters across America sent last Tuesday, which is that the vast majority of Americans are experiencing severe economic strains and still feeling the effects of inflation,” Murphy said. “There could not be a worse time to impose a new $9 toll on individuals who are traveling into downtown Manhattan for work, school, or leisure.”

But Hochul stressed that drivers who make less than $50,000 a year would be eligible for a 50% discount and that the toll rates will be lower during off-peak hours to encourage overnight deliveries.

The revised congestion pricing plan is expected to go before the Metropolitan Transportation Authority board for approval next week.

State officials have said that the revised plan is unlikely to need a repeat of the time-consuming environmental review process because, when the MTA board voted 11 to 1 in favor of congestion pricing in March, it was for tolls ranging from $9 to $23.

After the expected MTA approval, the state and city will then ink an agreement with transportation officials in the Biden administration, who have been supportive of congestion pricing.

The toll plan is expected to go into effect in January.

Hochul had been under pressure to move on congestion pricing from transit advocates and state lawmakers seeking funding for badly needed upgrades to the transit system, like the expansion of the Second Avenue subway line and installing modern subway signals and elevators in 23 stations.

Not all motorists would be socked with higher tolls.

While all the details of the new pricing structure were not immediately disclosed, NBC News reported in March that government vehicles would likely get full exemptions.Â

The full $9 toll would not be in effect for taxis, but drivers would be charged $1.25 a ride. The same policy would apply to Uber, Lyft and other rideshare drivers, though their surcharge would be $2.50.

Most drivers entering Manhattan’s Central Business District, which stretches from 60th Street all the way down to the southern tip of the Financial District, would have to pay the toll.

The full daytime rates would be in effect from 5 a.m. to 9 p.m. each weekday and 9 a.m. to 9 p.m. on weekends.Â

Only one toll would be levied each day, which means any motorist who enters the area, then leaves and returns, would be charged only once that day.

Proponents of the plan said congestion pricing would reduce the number of vehicles entering the most congested parts of Manhattan by 17% or about 153,000 cars.

They also predicted that congestion pricing would generate $15 billion that could be used to modernize subways and buses.