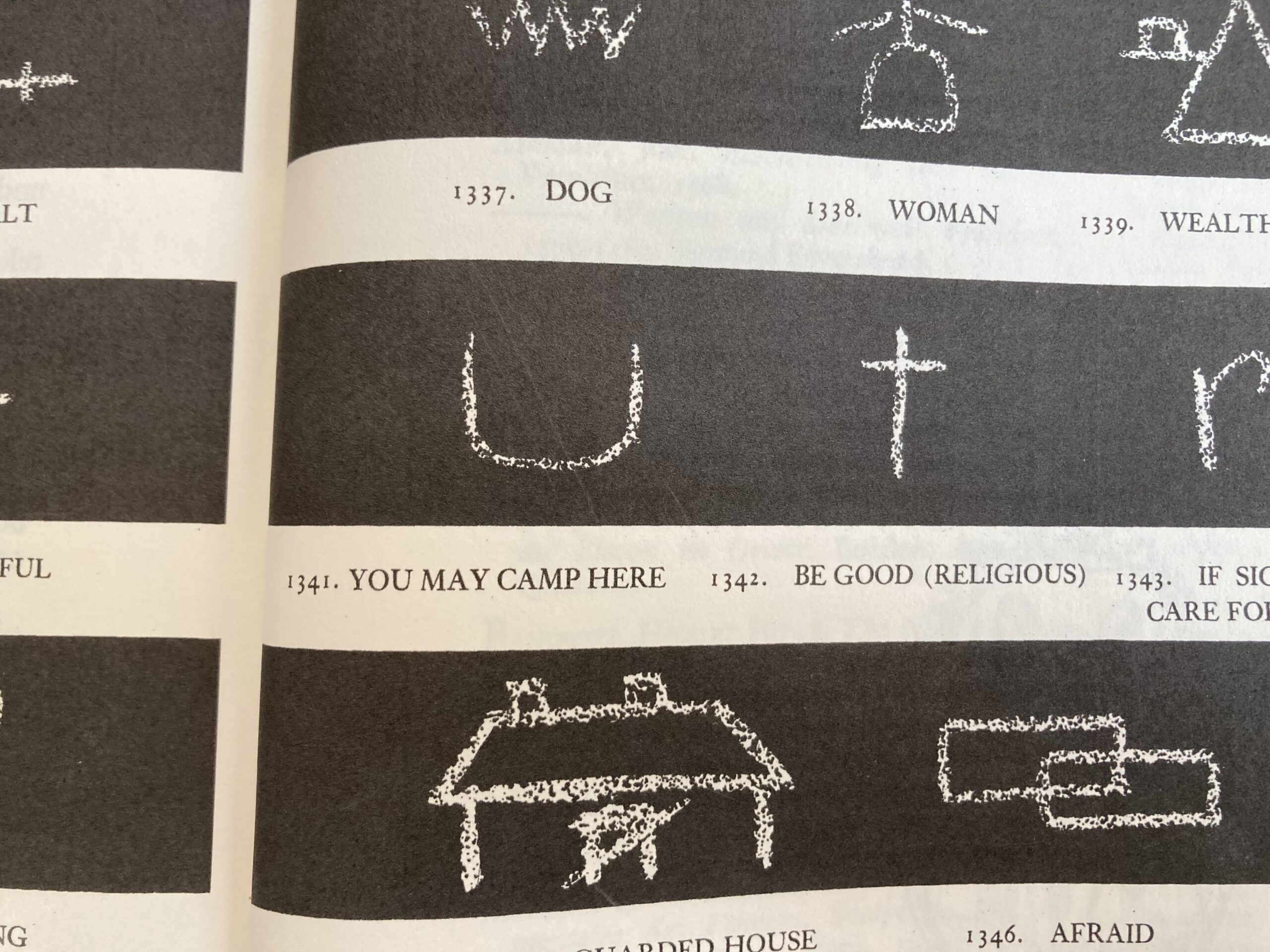

From Ernst Lehner’s Symbols, Signs and Signets.

For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Sara Gilmore’s poems “Mad as only an angel can be” and “Knowing constraint” appear in the new Fall issue of the Review, no. 249. The poem she discusses here, “Safe camp,” is published on the Daily.

How did this poem start for you? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

Originally this poem began with the lines “Delay and pressed the reeling available / Would-be constant down this inhabited suddenness.” It never troubled me that the words together didn’t make sense or that I didn’t yet know what they were pointing to—I thought of them as an assembly of beautiful raw material to work with.

As I continued to work on the poem, the image that rose to mind was a ditch along a narrow country road I often strolled down with my son near Mairena del Aljarafe when we lived in Spain. It was filled with trash and reels of unwound VHS tapes. We walked by it hundreds of times. The poem began to grow around the word “reeling”—the “real” along with everything the real is not, the dizzying motion of “reeling,” Anne Carson’s notion “under this day the reel of another day.” This figure of reeling gave into the poem’s circuitry as a whole—the way it shorts out as if its webbing could open to reveal layers underneath, suggesting a kind of sinkhole that either delivers us from or constricts us into a frame of reality that runs along our lives eternally. For me, these sinkholes are dangerous and fascinating.

This is one of the poem’s anxieties—the possibility of a circularity of circumstance or time in which what I’m living today could be the actual present, or a day I lived long ago, or a day I haven’t lived yet at all.

The poem surfaced into clarity in the lines that, in the version published here, appear first. “I was still but tried, in a burst it’s all lit up by.” I like to think the original lines are still there—what my friend Timmy calls the rungs of the ladder that we’re no longer standing on but got us here.

What were you listening to, reading, or watching while you were writing?

The day I started writing, I read Wallace Stevens’s “A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts” for the first time, my son’s stepbrother was born an ocean away, and I went on a walk with my son in Hickory Hill Park in Iowa City. It was April Fools’ Day, a year into the pandemic. My son made a set of cardboard claws to wear. That’s the day the poem emerged, but of course many other days and markers are also embedded into it. I date all the poems I write, maybe to have some anchor in what feels like a sway. I take pictures with my phone of the passages I read, the places I go, people I’m with. With all this underneath, the finished poem can seem like a little white flag waving surrender over a frighteningly infinite and invisible mountain—how do you get at that? I don’t know. I keep trying. What I like about “A Rabbit as King of the Ghosts” is the strength it finds in intimacy. It’s not afraid to say things like “In which everything is meant for you / and nothing need be explained.” In “Safe camp,” I think I got a little closer to conveying strong emotion and feeling outside explanation—strong love, strong belonging, without a tether to fixed place or meaning, the resistance to have those things outside any formal permission.

How did writing the first draft feel to you? Did it come easily, or was it difficult to write? Are there hard and easy poems?

Writing a poem is the easiest and hardest thing in the world to do. Easy in the sense that it’s a human impulse, like singing in the shower, and difficult as far as the huge emotional and intellectual toll it takes. I wrote “Safe camp” quickly, first in my head and then on my phone. I repeated its lines over and over to myself. Two days later I had my second COVID vaccination in Washington, Iowa. When I drove back home, I had a sense of calm, and I knew the poem was good.

How did you come up with the title for this poem? Were there other titles you thought about? Why didn’t you go with them?

“Safe camp” belongs to a cycle of serial poems written around the symbols that itinerant communities have historically used in the U.S. After the Great Depression, as people (many of whom were teenagers) moved across the country looking for work, they would leave scratch marks or markings in chalk outside the places they visited, to tell others what those places were like. For many years I’ve had a copy of Ernst Lehner’s Symbols, Signs and Signets, which includes a catalogue of these visual symbols and verbal descriptions of their meanings: “Owner is in,” “Keep quiet, “Bad dog,” “Safe camp.” There’s something flat and solid about these descriptions that contrasts with the way I write.

So, I would write as I do but title the poems in the order the symbols appear in Lehner’s book. And I knew where I was. Placing any material or element next to one another generates a force field, which can be very unexpected and wonderful—like a safe camp, in fact. But that notion of safety also signals the privilege of authority, signage, the ability to grant permission. I think that bled into the line “In the quiet permission / I took my unit of heart and wondered if it was enough.”

I was also influenced by Joyelle McSweeney’s The Red Bird, which includes many different poems with the title “The Voyage of the Beagle.” This is something I stole from her—I actually have several poems titled “Safe camp.”

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished after all?

This iteration of the poem is probably finished. I read Benjamin Krusling’s Glaring many times around the time I wrote “Safe camp.” He has a gorgeous poem at the end of that collection that begins, “first there’s love…then there’s synchronized time.” And, in Triple Canopy, another poem that begins “it’s love , but there’s no time.” In both poems, variations on the lines are repeated in different orders. I asked Krusling, during a Q&A after one of his readings, about the relationship between these two poems, and he had this beautiful idea of a poem’s mutability—that it should never become an artifact, closed-off, museum-displayed. And that the most important things must be said many times in many ways. I’m interested in how this idea contrasts with the fixity that the page and publication provide.

Poems can also gather great force in their immutability, like the transformations produced by the repetition in chant. That’s what I was thinking about in the lines “An artifact // Gathered and became immobile, and even so / Changed year to year until its recognition fell to wind itself.” “Fell” then shifts to “felt” in the lines “I felt myself. I felt myself inhabiting it so I felt myself.”

Did you show your drafts to other writers or friends or confidants? If so, what did they say?

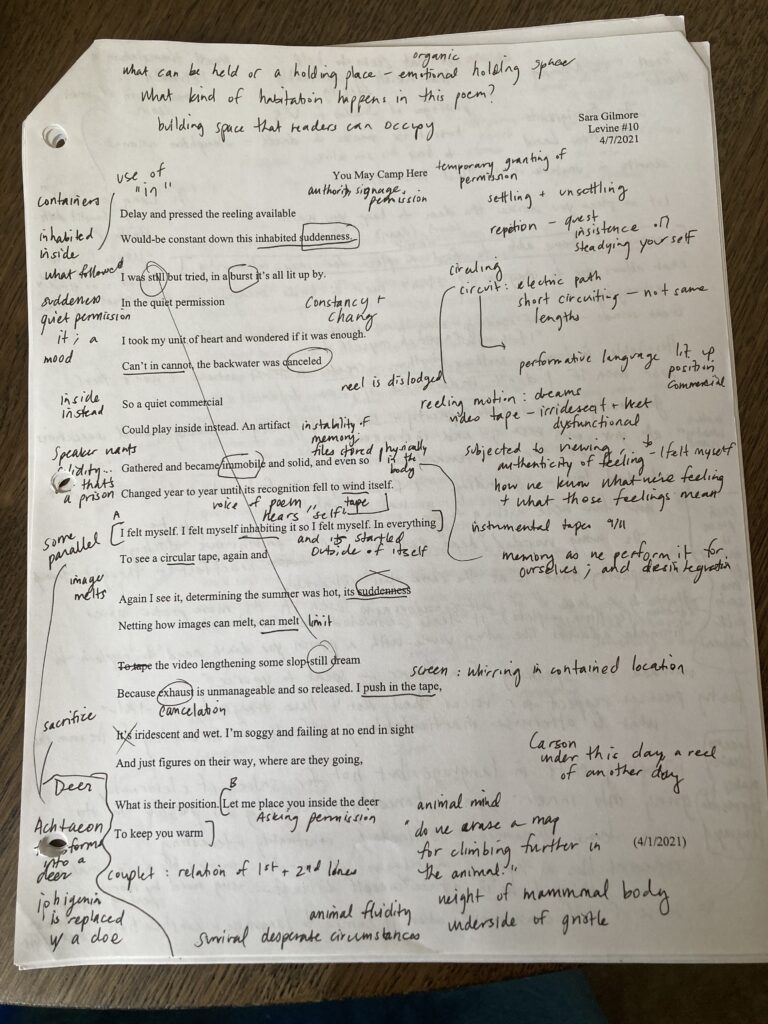

I workshopped this poem with ten other poets one week after I wrote it. My notes from that session have fragments like “voice of poem hears ‘self’ and is startled outside of itself” and “memory as we perform it for ourselves, and disintegration,” “whirring in contained location.” There is something about an “animal mind” and reference to the “weight of mammal body” and the “underside of gristle.” There are recommendations for other poets, like Wyatt and Petrarch, who wrote poems including deer. Talking about this poem with those poets was like becoming aware of the aliveness of a shared mind.

Sara Gilmore is a poet and translator. She teaches at the University of Iowa and works as a phlebotomist.