For our series Making of a Poem, we’re asking poets to dissect the poems they’ve published in our pages. Nora Fulton’s poem “La Comédie-Française” appears in the new Spring issue of the Review, no. 251.

How did this poem start? Was it with an image, an idea, a phrase, or something else?

I wrote this poem in September 2024, but it was a reflection of a three-day seminar I’d attended the month before. The seminar, organized by two brilliant friends, Matt Hare and Sam Warren Miell, was about the French film production company Diagonale, and focused on the work of its central director, Paul Vecchiali. Of the films we watched, Encore and Corps à cœur were especially on my mind while writing. Both are romantic melodramas, but they undercut that tendency in lots of interesting ways—I think I find them moving precisely because they undercut that part of themselves. The seminar focused on the way that Diagonale functioned as a collective of people who would take up different roles in each film, both in front of and behind the camera. This was likened to the troupe established by Molière, to which the title of this poem refers.

Were you thinking of any other poems or works of art while you wrote it?

At the time of writing I was thinking quite closely alongside the poetry of the Swiss Francophone author Philippe Jaccottet. I had begun reading and translating his early poems during the summer, mostly just for myself—I was working on them between sessions of the seminar, and continued this work into the fall. I was particularly enamored with the way Jaccottet uses hesitation as a formal device in both his poetry and his journals (the incredible translations of which, by Tess Lewis, I was devouring during these revisions). It’s not easy to write hesitation without seeming either arrogant or naïve. How can one hesitate in the field of language, at all, anyway? But Jaccottet finds ways to write through a reticence that manages to fully surrender to knowing that it has no idea what it is reticent in the face of, as in his journal entry for May 1971. “I write exactly as I have said one should not write. I am not able to grasp the particular, the private—the exact details escape me, slip away; unless it is I who shies away from them.”

Where did you write this poem?

In the front room of my apartment in Montréal. Right now it looks like this.

Do you have photos of different drafts of this poem?

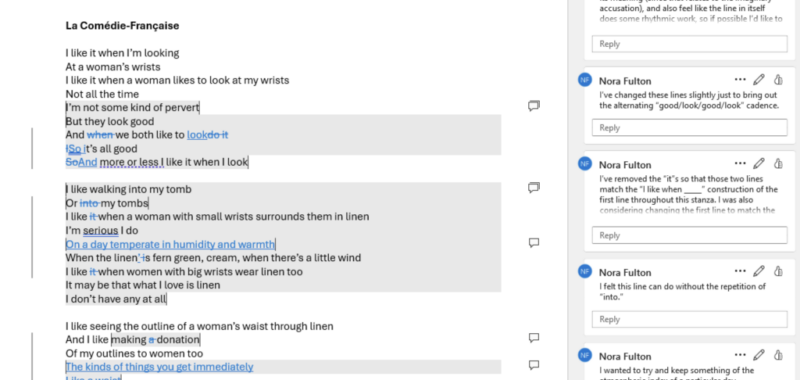

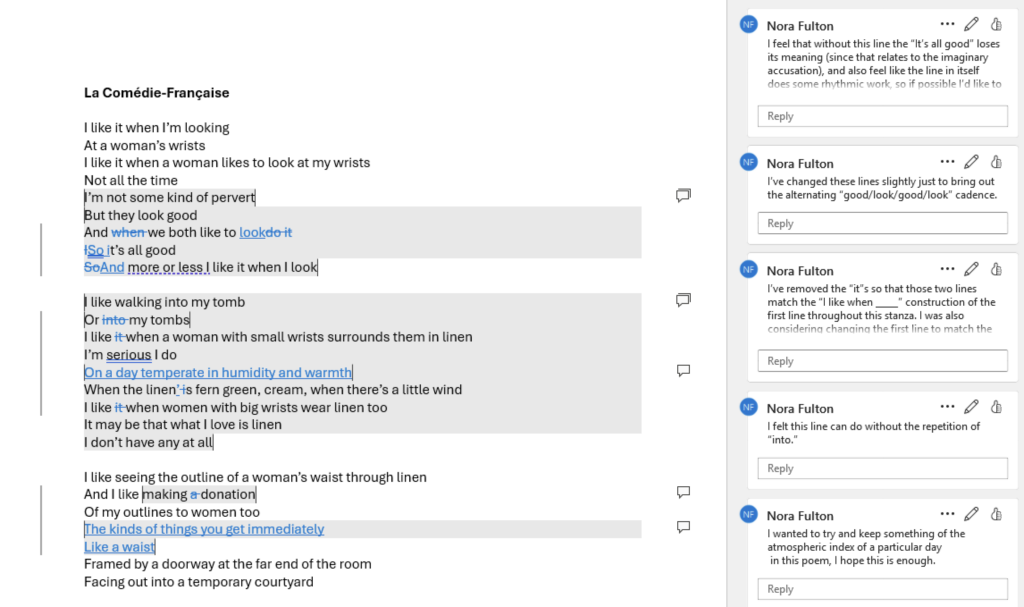

The first version of “La Comédie-Française” that I submitted to the Review went through a very heavy initial edit, to the point that that draft no longer seems relevant to the form the poem eventually took in print. The essence of that first edit was an incredibly perceptive removal of various avoidant comedic detours, which pared the poem down to central gestures I hadn’t noticed on my own—a pivoting away from and back into lyric transparency, and an attempt to make vernacular speech do something interesting aurally. I can supply two later drafts near the end of the editing process, where I feel like I found some solutions to the many problems I’d created for myself.

In this draft (which I think was the third), I’m revising a version sent back to me from a previous editor, so you see only my responses to their changes. The “On a day temperate …” line had been cut initially, and I felt that something beyond the subjective—some register of external specificity—was needed in such an internal piece, so I added that back in. There had also been many cuts made to the third stanza, and as a result I thought that part of the poem lacked coherence, so I restored lines there as well. I also cut articles and prepositions where I could, some of which were later reinstated—maybe I got a bit zealous after how productive the paring down had been. The penultimate line of “Shade, that is” had originally read “More shade that is”—it had been cut in the first edit, but was reinserted here. While the repetition of “more” originally came from the spirit of self-correction the poem begins with, I no longer felt that it needed to end in that register, and wanted to temper the pull of the idea that it is the shadows that grow close, rather than anything else.

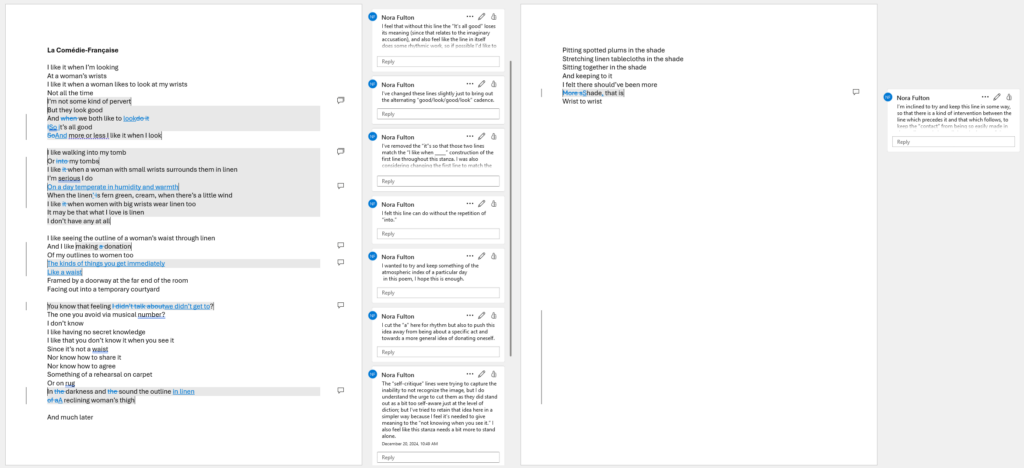

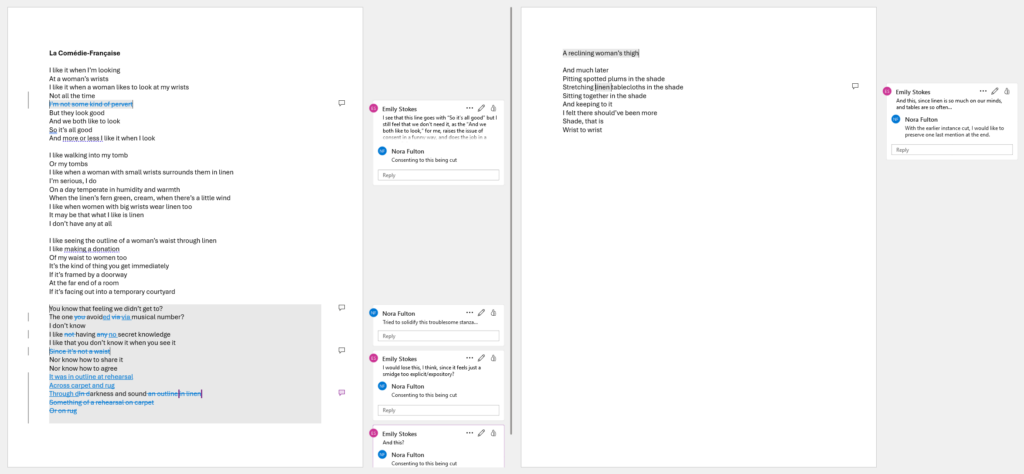

A couple of drafts later, it’s the fourth stanza that has become the issue. By that stanza, I wanted the gaze of the “I” to have traveled from tranquility and light to darkness and noise, and that movement was not easy to render without overwriting. The stanza’s first line shifts from a feeling of “I didn’t get to” to a feeling of “we didn’t get to”—before that, it was a feeling a “you” avoided, and in this draft the pronominal attribution is removed altogether—the feeling is said to be impersonally “avoided via musical number.” In the published version, it is again a “we” that is doing the avoiding. Surely there’s a kernel of inane psychologism in these decisions on my part, but I also think there was a real question of where to go from the hyperfocus on the “I” that the poem starts with. It has to go somewhere else. In the third stanza the “you” functions as a universal “you,” unmediatedly perceiving an outline and immediately knowing what it is an outline of is said to be something “one does” in general. Then in the fourth stanza, the “you” shifts to something more specific, but is still trying to continue talking about that universal. The “I / you” dynamic is hard to find an exit from, and probably I didn’t quite accomplish that here. But neither did I feel that simply leaving out pronominal attribution would be a solution— that would feel cheap to me. So I went with a “we” that could be both a container for the “I / you” and for the generality that is implicit in the idea that something like linen could be something like an index of something like women.

Also, that “I’m not some kind of pervert” line got cut. Ah, well.

When did you know this poem was finished? Were you right about that? Is it finished, after all?

I revise a lot. Way too much. If I could, I think I would go back to every book and poem and essay I’ve ever published and touch them all up, so they accord with where I’m at in the present. Sometimes that touching-up is just alternating between two or three or four changes, and one of them occasionally strikes you as a novel solution because you’ve forgotten you’d already tried it, just as you had with all the others. But is the finished version then the poem, plus the oscillation around each such point of indecision? I don’t think so. That’s why Jaccottet’s hesitation interests me—revision is basically just hesitation. But the goal is to make something that’s revised/revisable and true. I think that poems are finished when the poet’s attention finally wanders away from them and onto some other revisable thing. Which means, they’re finished when you don’t hesitate in your looking back on them.

Do you regret any of these revisions?

I do wish I could have found a way to keep some element of the “I’m not some kind of pervert” line. The idea of popping out of this melodramatic lyrical mode to give a proviso like that still makes me laugh, and usually something that makes me laugh in a poem is something I want to preserve. When I was writing “La Comédie-Française” I had in mind the limits that are placed on the possible articulations of the desires of women like me—limits that we put on ourselves, too. I ended up cutting that line based on editorial feedback, and I consoled myself in thinking that the poem as a whole could be my response to that idea. But, from a certain point of view, writing this piece could be my way of putting it back in.

Nora Fulton is the author of three books of poetry. Cuckoo’s Low Reel is forthcoming from Hiding Press this spring.