It’s normal, in September of an election year, for Anne Dover to feel stressed. This week, the 58-year-old elections director of Cherokee County, Georgia, has been drowning in absentee-ballot applications and wrangling new poll workers. What isn’t normal, though, is her looming sense of dread. What if this time, Dover sometimes wonders, things get even worse?

Four years ago, when Donald Trump was seeding doubt about the election, Dover’s community outside of Atlanta came unhinged. People protested as she and her team met before certifying the county’s votes. They took photos of Dover’s car; they followed her home; they left threatening voicemails; someone even called in a bomb threat to her office. The protests didn’t make much sense—Trump had won Cherokee County by almost 40 points. But sense had nothing to do with it. “People just really were so unhappy about the results, and they thought they could bring about change by being vocal,” Dover, a registered Republican, told me.

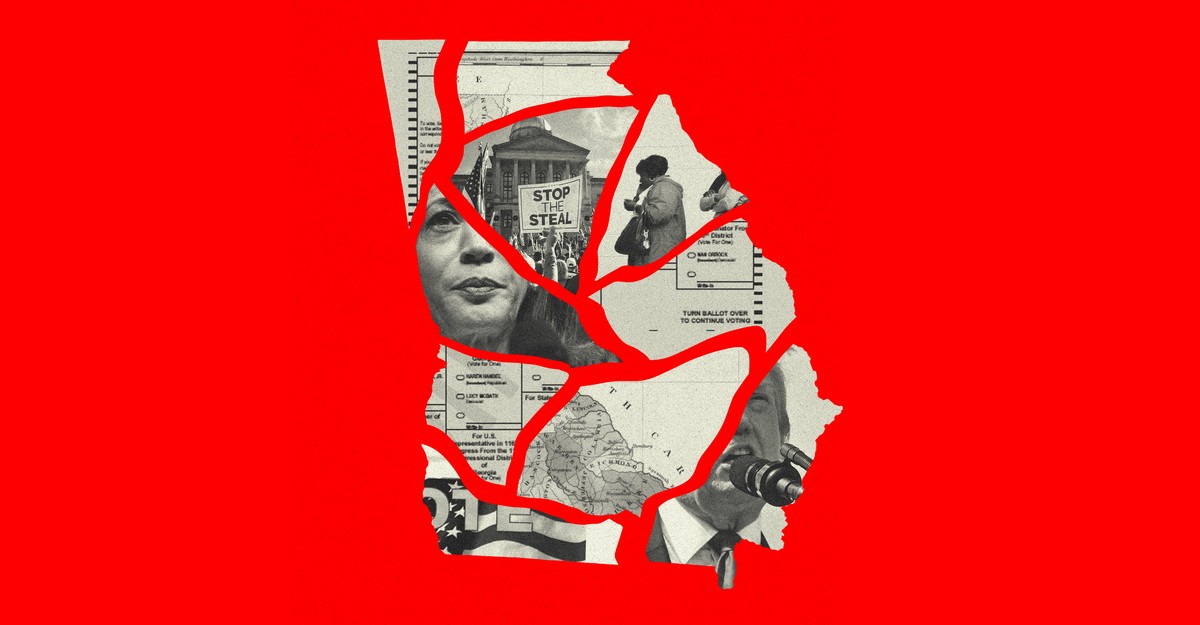

Even amid all that pressure and tumult, most state and local elections officials in 2020’s electoral battlegrounds refused to go along with Trump’s bogus claims of fraud. This time around, though, Trump’s allies have a more coherent strategy. In the run-up to November 2024, they’ve sought to take control of state and local boards, and, in Georgia, are establishing the fundamentals to bring about even more election chaos. On the state board, a new far-right majority is changing the rules mere weeks before a national election that might hinge on Georgia.

The election-denial mindset comes from confusion about the voting process, combined with prolonged exposure to a vortex of misinformation. Almost one-third of Americans tell pollsters that they continue to believe that the 2020 election was stolen.

Dover’s husband, Dwayne, is one of those people. “He’s a good guy,” Dover told me. “We just don’t talk about it.” But he agreed to explain his thinking to me. “I’m not an extremist,” Dwayne told me. He believes that his wife and her team acted with integrity in 2020, and that the protesters who threatened her then were “total nutjobs.” But there were problems in Fulton County—which includes most of Atlanta—and probably in some other states, Dwayne maintained, which is what makes him believe that Trump may actually have won the election in 2020. “There are crooked people out there,” he said. “Sad to say, but that’s just a fact.”

This dissonance is why election denial in America feels like a stubborn genie refusing to slide back into its bottle—and Trump and his allies are preparing to draw it out again. In November, the Republican nominee will almost surely win Cherokee County. “But if he doesn’t win Georgia,” Anne told me, “I am very fearful.” So is Dwayne. “They’re gonna lose their minds,” he said.

American elections are, objectively, bewildering. No two states run theirs the same way. Fifty sets of statutes and timelines govern our voting processes, which are, in turn, overseen by another 50 vexingly different combinations of elections personnel, including, but not limited to: elections directors, probate judges, commissioners, board members, auditors, county recorders, superintendents, sheriffs, and secretaries of state.

In many Georgia counties, the setup looks like this: An administrator such as Dover runs county-level elections and reports to an election superintendent, which, in her case, is a local election board. Those boards follow rules set by the state board. Overseeing the whole election process is Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, the GOP official whom Trump once failed to strong-arm into “finding” 11,780 votes. Raffensperger used to lead the central board, but after the episode with Trump, Republican state legislators deemed him untrustworthy and removed him from the panel.

This state board currently consists of five appointed members—one Democrat, a Republican-appointed chair, and three outspoken Republican members whom Trump clearly views as an extension of his own political operation. At a rally last month, the former president called the three his “pitbulls” for victory; one of the pitbulls in attendance, Janice Johnston, waved from the crowd. She recently created an unauthorized account on X for the board, in which she mischaracterized the board’s role in elections, according to reporting by Lawfare. There had been drama earlier in the summer, too, when a watchdog group sued the board for allegedly violating the Open Meetings Act. (Janelle King, one member of the board, has repeatedly denied that she and her fellow Republicans violated the law.)

This summer, the board’s Republicans—opposed by the panel’s chairman and the lone Democrat—passed changes to Georgia’s election-certification process, including one rule that allows local board members to conduct a “reasonable inquiry” into results before certifying them. A similar new rule gives board members powers to “examine all election-related documentation” beforehand. Republicans on the board argued: Why not?

The rules would allow every county board member “to see whatever they need to see” to feel confident signing the certification document, King, the most recent member appointed to the panel, told me in an interview. Before being appointed by the Georgia House speaker, King had been a star commentator on the local Fox affiliate, and a conservative podcast host. She represents a new sort of election official, a political partisan whose service is also boosting her public profile.

Public comments have overwhelmingly opposed the rule changes: 11 state legislators and nine nongovernmental organizations submitted protests to the board, according to the Citizens for Responsibility and Ethics in Washington. Even if partisan local officials can’t throw out vote counts, election experts fear that the new rules could be used by rogue board members as an excuse to delay certification—and for unhappy voters to pressure the officials who won’t play along.

Delay is a gift for a chaos agent like Trump, who, if he loses the presidential election, will likely be desperate to stir up trouble. The fear is not so much that the losing candidate will somehow end up swearing on the Bible in January, David Becker, the founder of the nonpartisan Center for Election Innovation & Research, told me. Safeguards exist to prevent that. The real concern is what could come before. These rules, he said, enable the loser “to falsely claim an election was stolen so he can raise money, and incite anger and violence.”

The state Democratic Party and the Democratic National Committee filed a lawsuit against the board alleging as much. (The trial is set to begin October 1.) “If Trump loses [nationally], you can guarantee they’ll do what they can to slow things down,” Becker said. The former president has already demonstrated his familiarity with the state election board—and everyone saw what he tried to do with Raffensperger in 2020. “Do we think he will have any qualms about calling each and every one of them if he loses,” Becker added, “and trying to pressure them to raise unfounded questions about his opponents’ victory?”

Boards are not supposed to slow-walk certification. Georgia county election boards are legally required to certify the results by a deadline, which, in this case, is November 12 at 5 p.m. ET. The board’s role is, in other words, a formality, without any room for discretion. Many Americans may misunderstand this, just as Trump’s supporters misunderstood that Vice President Mike Pence’s sole constitutional role on January 6, 2021, was to ceremonially accredit the election’s results. In Georgia, the path for contesting an election runs through the courts—and that can only happen once an election has been certified.

King assured me that all this anxiety is overblown. Certification is not a challenge “that we feel will be an issue this time,” she said. But some of her fellow officials are giving the opposite impression. In May, Julie Adams—a Republican Fulton County election board member and a member of the election-denialist group Election Integrity Network—filed a lawsuit asking a judge to declare that a board’s certification duties “are discretionary, not ministerial, in nature.” (The lawsuit was dismissed on a technicality this week, but Adams can refile.)

With seven weeks until the election, Georgia’s state board keeps trying to change the rules. Right now, members are weighing 11 more regulations that would take effect in this election. One of them would require workers at every polling place to hand-count ballots after polls close on Election Night, and make sure they match the number of ballots recorded by voting machines. Hand-counting is a normal part of election recounts, but “there is no legitimate election-integrity reason to require this or even to want it” in this case, Becker told me. Humans are already demonstrably worse at counting ballots than machines. Now imagine a group of 75-year-old volunteers, fresh off of a 16-hour shift, tallying results for multiple races late into the night. Their totals would almost certainly be wrong. If someone is looking to hatch a new conspiracy theory, you can bet they’ll start with those discrepancies. (Some of Dover’s poll workers are already threatening to quit if this rule is passed, she told me.)

The state board will meet on Friday to vote on the proposed regulations. If they’re approved, they will involve, at best, an unnecessary last-minute scramble for election directors like Dover. At worst, they could create glitches and delays that are open to exploitation by a frantic presidential campaign. In the Georgia Association of Voter Registration and Election Officials’ August letter, the group’s president, W. Travis Doss, urged the board to reconsider its action: “In a time when maintaining public confidence in elections is more important than ever, making changes so close to Election Day only serves to heighten concerns and fears among voters.”

Anne Dover, in Cherokee County, considered protesting the new rules at the state board’s meeting on Friday but decided against it. “I just feel like it’s a waste of my time,” she said. “They’re going to do what they want to do.”

King insists that none of the new rules are intended to undermine voter confidence in elections. Like Dwayne Dover, she pointed to 2020 errors in Fulton County, and said that the board is simply helping to prevent a recurrence. It’s true that election workers made some logistical errors, and miscounted small batches of ballots, that year in Fulton County, which is Georgia’s most populous county and votes reliably for Democrats. But those errors were not caused by fraud, according to the independent monitor who oversaw them that year, and were not significant enough to change the county’s election outcome. (Monitors will be in place again this year.)

The professed good intentions of the Republicans on the board are difficult to believe, given that election experts and officials on the ground have been begging them to please, for the love of God, stop making rules. Instead, the board is taking many of its cues from Republican activists—which is “like having a medical issue and asking your car mechanic what to do,” Nancy Boren, the director of the Muscogee County elections board, told me.

Ultimately, of course, intentions don’t matter. Actions do. And even as some local election officials have tried to promote transparency through office tours and Zoom calls, agitators and conspiracy theorists have followed along right behind them, muddling everything up again. The result, of course, is that distrust in our most fundamental democratic institutions spreads wider and burrows deeper.

In Cherokee County, Anne Dover has been trying to calm people down. Every Saturday morning, she meets with activists from VoterGA, a self-styled “election integrity” group, to hear their concerns and clear up misunderstandings. At night, she responds promptly to panicked voter emails, and during weekend shopping trips to Costco, she listens patiently to the concerns of her neighbors. Because Dover believes that what’s true in Georgia is true of election denialism all over the country: Many of the people who believe the system is rigged really do mean well—including her husband. And all she can do is keep reminding them of the truth: Dover and the others working to run America’s voting system “are grandmothers, grandfathers, moms, and dads,” she said. “We are not there to steal an election.” Dwayne isn’t reassured. “We’re gonna find out,” he said, “in about 50 days.”