Notre-Dame Cathedral re-opened to worldwide acclaim last weekend after a massive fire ravaged the Parisian landmark in April 2019. French authorities still have not been able to pinpoint an exact cause for the fire, but a new analysis may provide insights into how to avoid such a catastrophe.

The beloved Gothic cathedral, built from wood, limestone, iron, and lead in 1163 along the banks of the Seine, was long the city’s top tourist attraction and the site of many iconic events in French political and literary history. Reconstruction and restoration, from spire to sanctuary, cost an estimated ₵700 million, or about $740 million.

While an official cause has yet to the determined, a new Harvard Business School case study examines the complicated series of mishaps and operational breakdowns that allowed a small roof fire to become a catastrophic blaze. The Gazette spoke to Amy Edmondson, co-author of the case study and Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at HBS, about what the fire has to teach us about preventing suchdisasters. Interview has been edited for clarity and length.

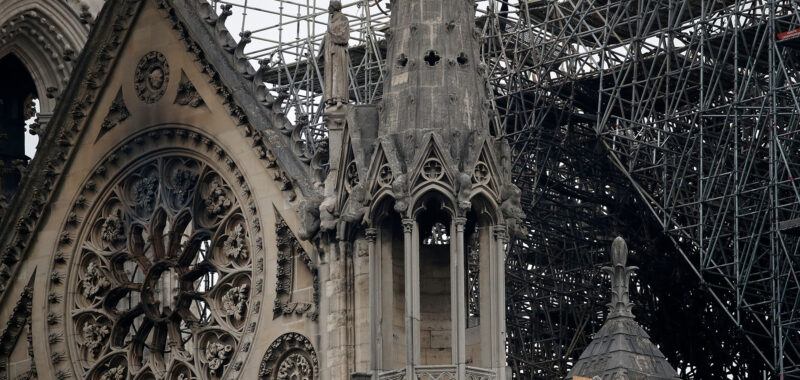

The Notre-Dame Cathedral reopened more than five years after a fire brought the entire Gothic masterpiece within minutes of collapsing.

Jeanne Accorsini/SIPA via AP Images.

Why were you interested in the Notre Dame fire for a case study?

Jérôme Barthelemy, a professor at ESSEC Business School in France, reached out to me to ask whether I was interested in co-authoring a case on the fire with him. I said yes, because, for me, this was a quintessential complex failure. I just wrote a book called “Right Kind of Wrong: The Science of Failing Well” in which I identify three kinds of failure — basic, complex and intelligent.

The “right kind of wrong” refers to intelligent failures, which are the undesired results of thoughtful experiments. But complex failures are a fact of life, and they are a phenomenon that when we are at our very best as individuals, but more importantly, as organizations, we can prevent. My research is about what more can we do to prevent tragic events like this, failures like this.

You delineate a number of poor decisions and troubling actions that may have contributed to the fire’s size and destruction. Five years later, why do you think French authorities still have no definitive answer on the cause?

I don’t know for sure. I know only what we could learn from published sources. With that in mind, I think the cause will likely remain elusive, because multiple factors — multiple culprits, if you will — were present. Multiple deviations from best practice are highlighted in the case — everything from workers smoking to a confusing fire code system to a built-in 20-minute delay between a call and the arrival of firefighters in the best of circumstances.

As with all complex failures, contributing factors interacted in complex ways. Identifying a single cause is rarely the best way to think about these kinds of failures. Every one of the small factors, like the workers smoking on the roof or storing electrical equipment near very old wood or doing hot work in the vicinity of the rafters, the way the fire alarm and warning system was set up, and the built-in delay is a potential contributing factor.

I can say confidently that it was devastating to all of those involved, both inside and outside the organization. So, they should be motivated to make changes, but identifying a definitive answer is unlikely.

Given that complex failures are caused a set of contributing factors, rather than one factor, it can be difficult to motivate, less change. What I argue in the book is that complex failures are on the rise because of the complexity of our systems. But they are theoretically and practically preventable. And the only way to prevent them is through vigilance — absolute commitment to best practices, a dedication to getting the little things right, all of them.

This is not as expensive or laborious as it might sound. It is about a habit of excellence, driven by the belief that rules and procedures matter, and deviations can escalate in dangerous ways. It’s far more expensive and laborious to clean up a failure like this than to run a tight ship, so to speak.

“Complex failures are on the rise because of the complexity of our systems. But they are theoretically and practically preventable.”

Could the fire have been avoided or done far less damage if one or two of these particular things had not occurred?

Yes, and that’s characteristic of complex failure. Often, all you need is to remove one or two of these contributing factors, and the failure is prevented. For example, if you didn’t have the fire department showing up 20 minutes after the call, you’d probably catch the fire before it turns into a devastatingly large fire. If you had very strict rules about where the electrical equipment goes, where smoking happens, etc. Take out any one of these factors, and it might have been a different outcome. I can’t tell you which, because we don’t really know.

More than 30 years ago, I was studying DuPont, which conducted multiple high-risk manufacturing activities but nonetheless had an extraordinary safety record, to understand how it worked. And I discovered that people in the company wouldn’t let an executive walk down the stairs without holding the banister; if you did that, you’d get reprimanded. You couldn’t walk around with an open coffee cup. No one at any level would put their key in the ignition of the car until they heard the click of each seatbelt. It was almost second nature.

Now, these seem downright silly. But their belief was: “Watch out for the little stuff.” If you apply that logic to the factory, if you aspire to have everything as close to excellent as possible, you can avoid the tragic perfect storms that cause complex failures.

You study leadership. Was this a failure of leadership?

Yes. By definition, leaders are accountable for the whole. Even if you could say, “Well, I didn’t do it; I didn’t smoke in the rafters.” Well, that is not quite right. As a leader, you did do it. You led in a way that allowed such deviations to occur. Sins of omission are every bit as important as the actual acts that may have contributed to the fire.

What issues do you want students to grapple with from this case study?

Exactly what we’re talking about. First, I want them to understand the difference between a basic failure — with a single, simple cause — and a complex failure, and then to take a close look at the organizational factors, which means managerial factors that allow such failures to happen. And then, I want them to think about what the leader’s role is: what they need to put in place to run an excellent operation. The lesson is that leaders can insist on the discipline and the vigilance needed to prevent complex failures.

Improbably, the building has been carefully restored in record time. Do you think anything else positive can come out of this situation or this tragedy?

Yes. The thing that’s positive that will, I hope, come out of it is that other important landmarks will be less vulnerable. This tragedy was a wake-up call for anyone who has responsibility for an important and fragile landmark, or any public good like a national park or even human safety in a complex operation. The insights do not apply only to ancient cathedrals.

Anytime you are leading or in charge of an important resource, especially anything related to human life, you have a responsibility for being vigilant and thoughtful, an encouraging voice, and for stress-testing your hypotheses rigorously. I think there’s a lot of prevention insight that comes from this case, and because of the emotional nature of that loss, it gets people’s attention and could make a difference in that way.

Source link