Yang Jie / Zhang Xiguang

Around half a billion years ago, in what is now the Yunnan Province of China, a tiny larva was trapped in mud. Hundreds of millions of years later, after the mud had long since become the black shales of the Yuan’shan formation, the larva surfaced again, a meticulously preserved time capsule that would unearth more about the evolution of arthropods.

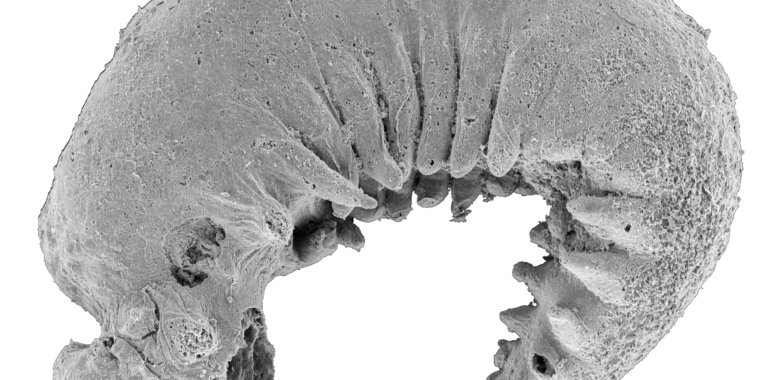

Youti yuanshi is barely visible to the naked eye. Roughly the size of a poppy seed, it is preserved so well that its exoskeleton is almost completely intact, and even the outlines of what were once its internal organs can be seen through the lens of a microscope. Durham University researchers who examined it were able to see features of both ancient and modern arthropods. Some of these features told them how the simpler, more wormlike ancestors of living arthropods evolved into more complex organisms.

The research team also found that Y. yuanshi, which existed during the Cambrian Explosion (when most of the main animal groups started to appear on the fossil record), has certain features in common with extant arthropods, such as crabs, velvet worms, and tardigrades. “The deep evolutionary position of Youti yuanshi… illuminat[es] the internal anatomical changes that propelled the rise and diversification of [arthropods],” they said in a study recently published in Nature.

Inside out and outside in

While many fossils preserved in muddy environments like the Yuan’shan formation are flattened by compression, Y. yuanshi remained three-dimensional, making it easier to examine. So what exactly did this larva look like on the outside and inside?

The research team could immediately tell that Y. yuanshi was a lobopodian. Lobopodians are a group of extinct arthropods with long bodies and stubby legs, or lobopods. There is a pair of lobopods in the middle of each of its twenty segments, and these segments also get progressively shorter from the front to back of the body. Though soft tissue was not preserved, spherical outlines suggest an eye on each side of the head, though whether these were compound eyes is unknown. This creature had a stomodeum—the precursor to a mouth—but no anus. It would have had to both take in food and dispose of waste through its mouth.

Youti yuanshi has a cavity, known as the perivisceral cavity, that surrounds the outline of a tube that is thought to have once been the gut. The creature’s gut ends without an opening, which explains its lack of an anus. Inside each segment, there is a pair of voids toward the middle. The researchers think these are evidence of digestive glands, especially after comparing them to digestive glands in the fossils of other arthropods from the same era.

A ring around the mouth of the larva was once a circumoral nerve ring, which connected with nerves that extend to eyes and appendages in the first segment. Inside its head is a void that contained the brain. The shape of this empty chamber gives some insight into how the brain was structured. From what the researchers could see, the brain of Y. yuanshi had wedge-shaped frontal portion, and the rest of the brain was divided into two sections, as evidenced by the outline of a membrane in between them.

Way, way, way back then and now

Given its physical characteristics, the researchers think that Y. yuanshi displays features of both extinct and extant arthropods. Some are ancestral characteristics present in all arthropods, living and extinct. Others are ancestral characteristics that may have been present in extinct arthropods but are only present in some living arthropods.

Among the features present in all arthropods today is the protocerebrum; its evolutionary precursor was the circumoral nerve ring present in Y. yuanshi. The protocerebrum is the first segment of the arthropod brain, which controls the eyes and appendages, such as antennae in velvet worms and the mouthparts in tardigrades. Another feature of Y. yuanshi present in extant and extinct arthropods is its circulatory system, which is similar to that of modern arthropods, especially crustaceans.

Lobopods are a morphological feature of Y. yuanshi that are now found only in some arthropods—tardigrades and velvet worms. Many more species of lobopodians existed during the Cambrian. The lobopodians also had a distinctively structured circulatory system in their legs and other appendages, which is closest to that of velvet worms.

“The architecture of the nervous system informs the early configuration of the [arthropod] brain and its associated appendages and sensory organs, clarifying homologies across [arthropods],” the researchers said in the same study.

Yuti yuanshi is still holding on to some mysteries. They mostly have to do with the fact that it is a larva—what it looked like as an adult can only be guessed at, and it’s possible that this species developed compound eyes or flaps for swimming by the time it reached adulthood. Whether it is the larva of an already-known species of extinct lobopod is an open question. Maybe the answers are buried somewhere in the Yuan’shan shale.

Nature, 2024. DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07756-8